Surviving Gates of Multan

One of the oldest living cities in the world, Multan is a significant example of old Islamic urbanization. While many historic Islamic cities have lost much of their original character during the twentieth century, Multan has survived remarkably intact, retaining the classic form of the medieval city encircled by its rampart and gateways. It is the entire urban fabric of the place that is historic.

Inside the walled portion -- archetypal form of old town -- one can still see beautiful bay windows with intricately moulded 'jharokas' in narrow streets or delicate brick work with geometric patterns and tile friezes on the facades of havelis. Meanwhile, modern Multan has expanded in all directions covering over 28 square kilometres of area. And with modernism have come related difficulties. "Problems like overflowing sewerage and a broken down water supply system, encroachments and pollution are taken as hazards of urbanization or attributed to lack of funds," says a resident of Gulgast colony.

Archaeologist Nazir Ahmed complains," the intelligentsia is inactive and people have no time for pursuits like preservation of historic and cultural heritage." The original defensive wall -- 40-50 feet high -- dating from the seventeenth century was demolished in 1854 after the British captured Multan but its lower sections survived. The present remains of the wall preserves the semi circular form of bastions at intervals.

The wall was reduced to 10-12 feet during the British period. It contained seven gates, of which Lahore, Delhi, Daulat and Khizeri gates have disappeared. Dilapidated Khuni Burj (Bloody Tower) named after the bloody battle fought here when British force stormend Multan in January 1848 still survives.

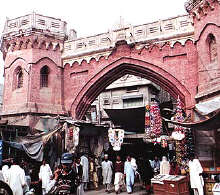

A circular road (alang) runs around the walled city connecting the surviving gates, Khuni Burj and Hussaim Agahi entrance. Three of the six gateways -- Bohar, Haram and Delhi -- were rebuilt in the latter half of the nineteenth century with pointed arches and castigated towers. All of them badly need renovation.

Once an imposing gateway, Lahori Gate existed even in the nineteenth century when Alexander Cunningham visited and wrote about Multan. It was damaged when the British annexed Multan and totally demolished in 1854. The new gate built on this site is a combination of two double story towers with a flat band above and is without much decoration. Haram gate comprises of two pylons on each flank, with a large four cantered pointed arch in the middle. The castigated towers on flanks are double storied. Delhi Gate, one of Multan's oldest landmarks, existed even before arrival of the British. The present gate was rebuilt during the British rule. Its construction is similar to Haram Gate except that its arch has a wider span. The gateways have been white washed and painted several times with water based earth colours and none of the original work has survived. The wooden doors have also disappeared. The gateways are surrounded and engulfed by encroachments, cubby-hole shops, hundreds of advertisements and hoardings.

As for the wall itself, its present condition is ruinous and at no place does it maintain its original shape. At most places, it is totally missing. Most salient portion exists between Daulat Gate and Pak Gate. Rows of houses and shops have been erected on the strip of land between the outer face of the circular road and the inner face of the wall, in the process concealing several notable historic features.

However ruined it maybe, the wall still defines the edge of the old city far more clearly than the circular road and is an immediate reminder of Mutlan's historic character. The circular road is in fairly good condition through its width and right of way has been considerably reduced due to unchecked encroachment.

Multani monuments face unsympathetic development, unsuitable repairs or general neglect. All the surviving gates should be cleaned, repaired and renovated to their original shape as far as possible, says Nazir Ahmed. They should be freed from all sorts of neon sign that hide more than they highlight.

The Antiquities Act 1975 and the Punjab Special Premises (Preservation) Ordinance 1985 are not sufficient to protect historic cities. A new concept for area conservation is required to be developed through government polices and public education. Towards this end, the departments of archaeology, Auqaf and civic bodies all need to work together to save what remains of a once glorious medieval Islamic culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment